- Frances McLeod of Forensic Risk Alliance will scrutinise Binance's anti-money laundering efforts.

- The three-year monitorship ushers in a new era for the world's top crypto exchange.

- Independent monitors have free rein to look at everything in microscopic detail.

Citigroup had one. So did Wells Fargo, Deutsche Bank, and Credit Suisse.

Now Binance has one, too.

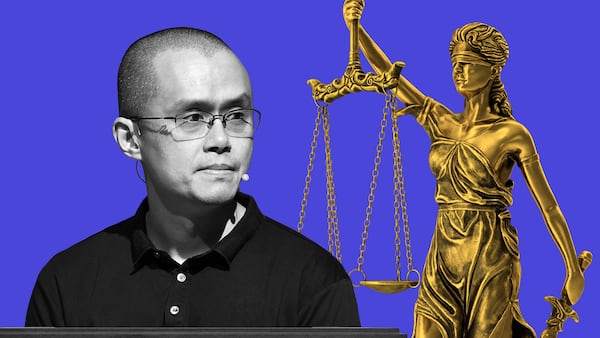

Changpeng Zhao may have created his cryptocurrency exchange to usher in a new era free of the pesky rules that have long governed finance.

But now Binance is a member of an august and exclusive club — it will operate with an internal watchdog scrutinising virtually every move it makes.

Microscopic level

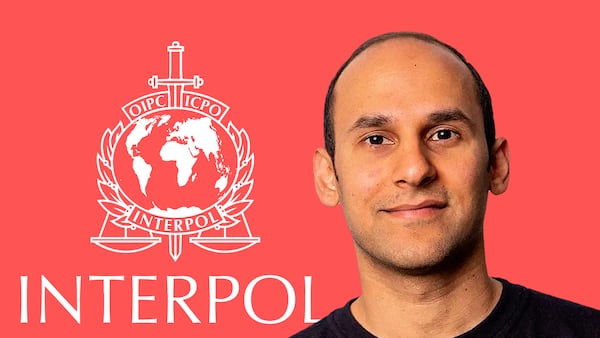

On Tuesday, Binance confirmed to DL News that Frances McLeod, the founding partner of Forensic Risk Alliance, will serve as its independent monitor.

Selected by the US Justice Department, she will supervise Binance’s anti-money laundering and know-your-customer practices at a microscopic level over the next three years. One former regulator likened them to a “financial colonoscopy.”

While this development sounds technical and painful — and rest assured, it is — the “monitorship” will force the world’s top crypto exchange to change its ways.

Ultimately, the company will have to prove it is stopping problematic transactions on its platform.

“In a case like Binance, a company should not get credit for compliance without sound empirical testing,” Brandon Garrett, a law professor at Duke University in North Carolina, told DL News.

“If the company can show that problematic transactions were caught then there is evidence the system is working.”

Independent monitors came into vogue following the global financial crisis of 2008. These in-house experts have become a fixture in banking, asset management, and even manufacturers and labour unions.

What is Forensic Risk Alliance?

Forensic Risk Alliance, a 25-year-old British firm known as FRA, specialises in dissecting multinational companies.

It has worked inside corrupt commodities firms, dodgy European banks, and advised the FBI’s counterterrorism unit tracing cryptocurrencies.

When it comes to Binance, McLeod has her work cut out for her.

‘Misconduct by employees will often find its roots in a flawed or dysfunctional corporate culture.’

— Neil Barofsky, lawyer

According to the Justice Department, Binance’s anti-money laundering, or AML, programme was so basic that it neglected to file a single “suspicious activity report” with authorities.

This is extraordinary given that Binance executed trillions of dollars worth of transactions and bagged $1.6 billion in profit between 2017 and 2022.

Anomalous trading patterns

For decades, banks, asset managers, and other financial institutions have been obliged to flag potentially illicit transactions as suspicious activity reports, or SARs.

To that end, finance firms employ armies of lawyers, accountants, data analysts, and industrial-strength “regtech” software designed to hunt for anomalous trading patterns and market activity.

The average bank spends $48 million a year on compliance measures, according to KPMG.

If a firm neglects to submit SARs to authorities, that itself becomes a red flag — it means the institution isn’t properly policing itself.

What will FRA do with Binance?

So what will FRA do to turn things around at Binance? Plenty.

According to a 2022 primer co-authored by McLeod, forensic monitors like FRA do a deep dive on company systems, records, and transactions broken down by business unit and geographic markets.

They look at everything. It’s like having an auditor combing through every payment you’ve ever made, or will ever make.

Monitors also help develop “remediation plans” that companies must implement to satisfy the authorities they have corrected their ways.

In the case of Binance, this means demonstrating to the Justice Department that its AML and KYC practices are up to snuff.

It doesn’t stop there. Monitors often tackle the less quantifiable reasons why companies go bad.

“Misconduct by employees on a scale that leads to the imposition of a monitorship will often find its roots in a flawed or dysfunctional corporate culture,” said Neil Barofsky, a leading lawyer in the field, in a report published by Global Investigations Review.

Dirty money

Barofsky said companies under monitorships typically have to show authorities they have reformed their culture substantially enough to minimise the risk of recidivism.

This is an exhaustive process involving retraining personnel, changing compensation policies, and setting the right tone at the top of management.

Given the scale of Binance’s wrongdoing, a culture change may well be in order. Last November, the company pleaded guilty to breaking US banking law by letting criminals and sanctioned organisations wash their dirty money on its crypto exchange.

Even after the company agreed to pay a staggering $4.3 billion in penalties and Zhao resigned — and pleaded guilty himself — it seemed clear Washington was demanding wholesale changes at Binance.

“Its willful failures allowed money to flow to terrorists, cybercriminals, and child abusers through its platform,” said Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in a press conference on November 21.

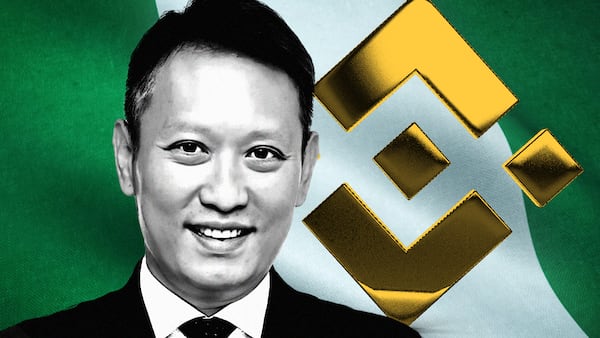

To be sure, Richard Teng, Zhao’s successor as Binance’s CEO, has vowed to make the company a compliant citizen of the global financial order.

He has promised to obtain the operating licences Zhao long eschewed.

And he reversed the founder’s cherished policy of not establishing a global headquarters, a decision that epitomised Binance’s online-only business model. The search is now on for a home base.

Binance said it is committed to investing resources to build a “best in class” compliance system.

“We want to set an example for the rest of the industry and inspire others to do the same — with a goal of making the digital assets space a safer and more secure place for all,” a Binance spokesperson told DL News.

And it is Binance that must pay the monitor’s fees, which can be considerable. Philip Inglima, a partner at law firm Crowell, estimates that monitor bills can cost firms at least $50 million over the course of three years.

Strict supervision

Yet as McLeod and her FRA team pitch camp in Binance wherever it may be located, Teng will be confronting the one thing crypto was supposed to obviate — strict supervision.

There’s ample irony in this development, of course. But Teng will probably be preoccupied with more pragmatic concerns.

The US Office of Foreign Assets Control has also selected another independent monitor to work alongside McLeod in Binance.

Sharon Cohen Levin, a partner at Sullivan and Cromwell who specialises in national security law, will watchdog the company’s efforts to comply with US sanctions compliance for the next five years, Binance told DL News.

Edward Robinson is DL News’ Story Editor. Joanna Wright is a regulation correspondent at DL News. Got a tip? Email them at ed@dlnews.com and joanna@dlnews.com.