- Should crypto bosses be called mafia bosses?

- A letter to our ombudsman suggested that they should.

- In this week's column, Robert Holloway argues that there are several reasons not to use the word 'mafia.'

Robert Holloway is a columnist and an award-winning ombudsman at DL News. Views expressed are his own.

A reader responded to my column “Let’s depose the kings of crypto” with a suggestion to call them mafia bosses. There are several reasons not to do so.

First is the risk of defamation. The principal meaning of mafia in the leading dictionaries of American and British English is a secret criminal society, notably in Italy, although the word was later used in the United States and other countries.

That is how our reader understood it. “Most, if not all of the people mentioned in the article are criminals or at least accused of committing crimes,” he wrote. “A better label for this group might be crypto mafia bosses.”

Pinning the label on an alleged criminal who turns out to be innocent may make a reporter liable for damages.

It is hard to defend a charge of defamation. Once it is established that the defendant published the offending words, the plaintiff has only to convince a jury that their reputation has suffered.

In English law, unlike some other jurisdictions, a plaintiff need not show that the words were malicious. It is no defence to say that they were meant ironically or in jest; or that they were intended to apply to someone else and published by mistake.

To call someone a mafia boss not only implies secret criminal organisation, it also suggests ruthless violence.

On November 20, a court in the Italian city of Vibo Valentia sentenced 207 members or associates of the criminal syndicate known as ‘Ndrangheta to terms of up to 30 years in prison.

Their offences included intimidating people by beating or shooting, threatening them with sledgehammers and dumping dead animals at their homes.

(The ‘Ndrangheta operates in the southern region of Calabria. Like the Sicilian Cosa Nostra, it does not use the word mafia to refer to itself.)

Juries tend to sympathise with plaintiffs who claim that their reputation has suffered. As recent cases in the United States show, they are sometimes prepared to award huge and punitive damages.

On December 1 a jury in Washington ordered Rudy Giuliani to pay $148 million for defaming two former election officials in the state of Georgia.

Giuliani, former lawyer to Donald Trump, falsely accused Ruby Freeman and her daughter Wandrea “Shaye” Moss of tampering with ballot boxes to steal votes cast for Trump in the 2020 presidential election.

Freeman and Moss said their lives were ruined by the accusations; they received death threats and were forced to move house.

Earlier this year, Fox News agreed out of court to pay almost $800 million to the Dominion Voting Systems company after falsely reporting that it programmed machines to transfer votes from Trump to his opponent, Joe Biden.

Last year, the radio host and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones was ordered to pay nearly $1.5 billion for defaming the parents of 20 children murdered in Sandy Hook elementary school in Connecticut in 2012.

Jones, who is appealing against the verdict, alleged that the mass shooting was a hoax arranged to whip up support for gun control.

Some media nevertheless use the word mafia in the looser sense of a clique, defined by Merriam Webster’s dictionary as “a group of people of similar interests or backgrounds prominent in a particular field or enterprise.”

Usually, however, they apply it to groups which are unlikely to sue, rather than to individuals.

A group of founders and early employees of payments company PayPal, a group that includes Tesla CEO Elon Musk and tech investor Peter Thiel, is often referred to as the PayPal Mafia.

Caitlyn Jenner, a trans woman and former Olympic gold-medalist decathlete complained in recent interviews of “a radical rainbow mafia” within the LBGTQ community.

The reference is sufficiently vague that no individual could claim to be defamed by it.

There are three common defences against a charge of defamation. The first is truth.

If you call someone a mafia boss and can prove that the description is accurate, end of story.

But it might not be enough simply to show that the person was, for example, guilty of tax evasion like the notorious Chicago mobster Al Capone.

The person could argue that he was defamed by your words if other people unfairly inferred that he was also ruthlessly violent.

The second defence is called privilege. This covers words spoken in parliament, which may be quoted verbatim in media reports without fear of legal action.

Third is public interest. Here the term means of benefit to society, and not what some members of the public might find interesting.

The weekly Economist invoked the defence when sued by the late Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi after he won a general election in 2001.

On April 26 that year, before polling began, the magazine published a cover photo with the headline “Why Silvio Berlusconi is unfit to lead Italy.

A court in Milan later ruled that it was in the public interest to allow The Economist its right to fair comment.

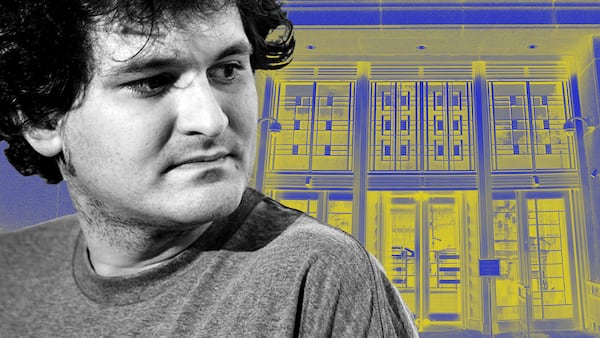

It is not clear, however, that it is in the public interest to describe Sam Bankman-Fried, for example, as a mafia boss when he is not.

Defamation aside, there are other reasons to avoid using the term. For a start it is overused.

The Italian examining magistrate Giovanni Falcone, who was assassinated by Cosa Nostra in Sicily in 1992, asked that the word not be applied to people and actions that “have little or nothing in common with the Mafia.”

Mafia is sometimes used as a term of political abuse.

Last month, the British Daily Express quoted an unnamed supporter of former prime minister Boris Johnson as blaming his downfall on “a mafia operation at the heart of the Conservative Party”.

Johnson stood down as party leader in June 2022 after six cabinet ministers and 51 senior officials resigned over his leadership.

He resigned as prime minister three months later and quit as a member of parliament in June this year after an inquiry into allegations that he misled the House of Commons.

Other tabloids used the word mafia in headlines to reports about a book published last month by one of Johnson’s staunchest supporters, Nadine Dorries, the former culture minister.

Dorries alleged that a secret group of Conservative lawmakers plotted Johnson’s ouster.

She also complained that “sinister forces” had thwarted his recommendation to make her a member of the upper house of parliament, the House of Lords.

Italians who lived for years with the threat of violence by organised criminal gangs sometimes object to media in other countries adopting the expression. They see it as making light of murderous violence.

In January, a headline in the British Daily Express said: “Mini-mafia housing association forced to return £25,000 to residents.”

In August, the same paper reported that “a wildlife crime charity has smashed a ‘mafia-type’ smuggling ring” that was poaching ivory in Africa.

Underlying all this is the question of the media’s role in society.

The media certainly have the right to comment on matters of public importance. In doing so they have at times helped to correct injustice or to bring about a change in the law.

The media’s defining role, however, is to report facts accurately and impartially. That enables readers to make informed judgements of their own.

Crypto journalists can better serve the public interest by exposing wrong-doers through well-researched investigations, than by denouncing them after they have been caught.

If you have an opinion about the media’s role, you can share it with me at robert@dlnews.com.