- Western central banks are at risk of debasing their fiat money.

- For rival nations, it will make sense to move away from dollars and euros.

- Blockchain-based currencies could be a solution for them, but don’t expect Bitcoin to be what they turn to.

- That’s according to Wolfgang Münchau in his latest column for DL News.

Wolfgang Münchau is a columnist for DL News. He is co-founder and director of Eurointelligence, and writes a column on European affairs for UnHerd. Opinions are his own.

The most difficult thing to understand in economics is fiat money.

I always found that the best way to look at money is in terms of a social contract — very much in the spirit of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the French political philosopher who invented the concept.

It is a contract between the state and the public. It is based on law, but more importantly on trust. We trust that the government and the central bank won’t debase the money through imprudent policies — as has been happening persistently since the global financial crisis — through various central bank policies, from quantitative easing to lending practices that would have been considered reckless until recently.

Thanks to blockchain technology it should be possible for investors to hedge against debasement — though I doubt that Bitcoin will be a suitable vehicle. With the advent of Bitcoin exchange-traded funds, and previously stablecoins, Bitcoin is increasingly turning into an asset of the dollar-backed global financial markets.

Herein lies an irony. Bitcoin should, in theory, offer a hedge against debasement, but its fortune is increasingly tied up with that of the dollar.

Modern forms of debasement are subtle. In the days of metal currencies, debasement was physical. The Roman denarius started off a pure silver coin weighing 4.5 grams. In the first centuries of the Roman empire the silver content was gradually reduced. By the third century, it was down to 2%. Monetary debasement preceded political decline.

Modern forms of debasement are far more subtle. Quantitative easing, the purchase of government and corporate debt by central banks, can turn into debasement through debt monetisation. QE allows central banks to control the long-term interest rate. There are circumstances where that would be a legitimate goal of monetary policy. In theory, it should be possible for central banks to buy bonds, and then sell them.

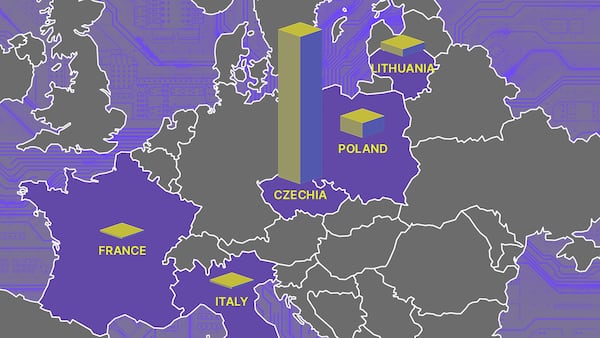

In practice, the buying proved easier than the selling. We see this in Europe right now. The European Central Bank held almost €5 trillion worth of assets in its balance sheet last year after two consecutive large purchase programmes.

It has since started to reduce its holdings from the first programme by not reinvesting in the bonds after they fall due. This year, the ECB will start phasing out its second big programme — the one it launched when the pandemic hit.

In theory, they should be able to get rid of all the bonds they hold. In practice that won’t happen. Most likely, they will launch the next asset purchase programmes before the old ones have been fully neutralised. The net result is that the central banks will monetise an ever larger proportion of government debt.

Debasement also comes in more subtle forms than outright debt monetisation. After the fall of Silicon Valley Bank last year, the Federal Reserve launched the Bank Term Funding Program.

It is offering one-year loans to banks against “collateral at par.” This refers to the value at which the banks bought the assets. Many of the bonds banks pledge as a collateral suffered a fall in prices after the Federal Reserve raised interest rates.

If they bought a US treasury bond or a mortgage-backed security in 2020 at $100 that is now trading at $80, the Fed would have previously lent them only $80. Now they are lending the full $100. They are lending against insufficient collateral — a no-no in central banking.

It is true that central banks have an obligation to support the economy and the financial sector in particular. But they need to do so prudently. The principles they should adhere to were best summarised by Walter Bagehot, the 19th century British journalist and essayist, who wrote that to “avert panic, central banks should lend early and freely to solvent firms, against good collateral, and at high rates.”

The qualifier “against good collateral” is absolutely critical. The Fed massively violated the Bagehot principle. And so did the ECB with its asset purchases it has been struggling to unwind in good times. This is debasement.

More recently, another form of debasement has started to occur, one that is far more troubling because it goes to the heart of Rousseau’s social contract.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the US and the EU immediately imposed a freeze on Russian reserve assets. The goal is understandable. They wanted to deprive Vladimir Putin of the means to wage war.

But the freezing of reserve assets constitutes a form of default on the fundamental promise that money entails. It is an intrinsic characteristic of money that it is a bearer certificate — one that central banks honour with no qualifications.

If governments intervene to freeze it, money loses this critical characteristic. Money then becomes a physical asset, like a luxury yacht or a villa.

The next logical step after freezing the money would be to pocket it. The EU is actively considering that right now.

At the December summit, Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian prime minister, blocked a proposed €50 billion aid package to Ukraine.

Several EU leaders are now calling for this money to be taken out of Russia’s frozen reserves to pay for Ukraine’s reconstruction. The superficial logic is that Russia should pay for the damage it caused. The problem is: it is not our money.

There are also legal difficulties, but I would not be surprised if the cash-strapped EU would ultimately find it a way to usurp the money. The US Congress is also withholding financial aid to Ukraine. The West is getting desperate.

We should not mince words here: this is a form of default.

Other countries will notice it. If the EU can do this to Putin when he invades Ukraine, they can do this to President Xi Jinping if he were to launch a blockade of Taiwan. And they can do this to a lot of other people too. Once a precedent is set, it is set.

Would foreign governments then still want to hold their reserve assets in dollars or euros? They cannot drive them down to zero. If a Chinese company sells a car to the US, it gets paid in dollars. It may change the dollars into yuan. But the dollars end up at the Chinese central bank, which has to invest it, most likely in US treasury securities. Any dollar investments are ultimately under the legal control of the US.

But there is still a lot that other countries can do. For example, there is no need for the five Brics countries — Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — to invoice each other in dollars or euros.

It would make both geopolitical and financial sense for them to trade in a currency that is not under the control of the US and EU. And they could also start divesting some of their existing dollar or euro reserves, and move them out of the jurisdiction of the US and the EU.

Blockchain technology will undoubtedly play a role. But a Brics central bank cannot simply invest its reserves in Bitcoin, which has become too dependent on the dollar markets — and thus on US jurisdiction. More likely, they will need to create their own crypto-asset, and then turn that asset into a legal tender.

All of this will take time. Right now, there is no available alternative to the dollar as the world’s dominating currency.

But it is debasement that makes it unsustainable. As we know from economic history, the unsustainable eventually ends.

What makes this so treacherous is the time lag between the moment you debase and the moment of truth. To the current generation of central bankers and politicians — and to the Roman emperors before them — debasement looks like a free lunch.

And we all know what happened to Rome.